INTRODUCTION

Each night at 9

p.m. sharp, Gretta, the rotund Swedish cleaning woman, stopped by my keypunch

station to chat with me. I was on my lunch hour, so I ate my lunch, while we

chatted a bit.

When I had eaten

my fill, I tagged along with Gretta, who truly loved her work, while she made

her cleaning "rounds." Her routine never varied, and it seemed disproportionately

consumed with the sanitization of each and every last ashtray in every last

office of every last cigarette-smoking manager, which seemed like it was just

about everyone in 1971.

Cleaning up after

everyone's habits had fed Gretta and her family of eight for 20 years--she figured

she'd be at it as long as she had a breath in her body. Gretta wisked through

the sales offices, then the vice-president's office, the CFO's office, and eventually

she made her way down the hall to the Executive Suite.

I usually stayed

with Gretta while she cleaned one or two offices, but one night she waved for

me to follow her as she walked to the opposite end of the long executive hallway.

Gretta quietly unlocked the door and opened it, stepping back out of the way

so I could enter first.

Not wanting to

spoil the surprise, Gretta left the lights off--directly across from the entrance

was an enormous floor to ceiling picture window that spanned two walls. She

left me in silence, and for a few moments I lost myself in the sound of nothing.

Thoughts of the Vietnam War, a recent marraige, and my choice to quit college

faded, and I took a long, deep breath--slow and sensous--the air rich with

beauty.

I gazed onto the

glittering expanse of the valley floor, taking in a view that filled every cell

of my body. The president's richly appointed office suite stood in stark contrast

to the drab, strerile environment where the rest of us worked. I felt a little

mischievous looking around the office "after hours," but still aspired to someday

advance beyond my current position as keypunch and computer operator.

I imagined myself

sitting behind the boss' desk running the show. The softly lit suite glowed

with warm incandescents, accenting the polished brass fixtures. It was a spacious

room, as big as several of the smaller offices combined. The beveled mirrors

and glass shelving made the room look even bigger than it's already generous

size. The furnishings were rich and sensuous--a deep red mahogany with burgundy

leather cushions--the kind of leather cushions that are tacked down with pea-sized

golden button tacks.

I stayed in the

office for several minutes minutes more, until it was time to get back to the

old grind--keypunch, output the data cards, and run them through the computer.

Each night, I performed the same routine, and when I was finished I'd neatly

stack all the blue-striped printouts on Rob O'Reilly's desk, where they would

patiently wait for him until he arrived at 7 o'clock the next morning.

I was 20 years

old with almost no professional work experience to my credit (unless you count

selling movie theater tickets), plus I was about to become a college dropout,

so I felt really lucky to have landed a job working with computers as a "computer

operator trainee" and keypunch operator.

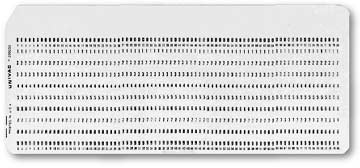

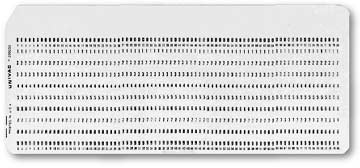

One

night about six weeks into the job, it was work as usual, just like any of the

other long, lonely "swing shifts,"except that night there must have

been a crimp in one of the punch cards. I stood alone in disbelief, while the

computer belched up hundreds of cream-colored 80-column punch cards, spewing

them into the room.

One

night about six weeks into the job, it was work as usual, just like any of the

other long, lonely "swing shifts,"except that night there must have

been a crimp in one of the punch cards. I stood alone in disbelief, while the

computer belched up hundreds of cream-colored 80-column punch cards, spewing

them into the room.

They collided high

in the air, pouring down all around me, leaving me knee deep in data. Eventually,

the data storm tapered off and the last, lonely punch card drifted gracefully

down to the gray, industrial carpet. The weary Univac 9600 coughed up the sum

total of its cards, leaving me, the innocent, novice computer operator down

on the floor facing the prospect of an all-night clean-up and sorting job.

While I was gathering

up the punch cards, I recalled the time when I was five years old, and I was

duped by my big sister for the umteenth time into playing this fun, new card

game called "52-pickup." I can't even count the number of times I fell for that

one. Eventually I would wise up, so she changed the name to "Round 'em up, cowgirl"--and

I was sucked in again.

This time "Trainee's

Surprise" had me picking up hundreds of cards instead of the familiar fifty-two.

I straightened the cards, placing them all face side up, weeding out any that

were bent or torn so that I could duplicate the information on them before placing

them back into the mix.

As I sat on the

floor, surrounded by a blanket of a thousand or more cards, I set about the

task of collecting, duplicating and sorting the mass of the mangled media. Silly

as it might seem, I was captivated by those 80-column punchcards. That's when

I started ruminating on how all "those little holes" worked.

This "happy" accident

and the night-long salvage operation set me on on a journey into a world rich

with digital information. That night back in 1971 I began my love / hate relationship

with computers. I had landed my first job as a keypunch and computer operator

for a large manufacturing firm where I worked on the second floor above the

factory, on the floor that housed the adminstrative offices. I began work at

5 p.m. and worked with a supervisor until 6 p.m., when all the lights on the

floor were shut off and everyone went home--except me. I was left to spend the

long, lonely swing shift hours reading the same data forms, night after night,

keying in all those meaningless numbers, with no one and nothing to keep me

company but the machine-gun clatter of my keypunch machine.

Punching, sorting

and analyzing data might not be a particularly appealing job to the average

20-year-old-flower-child-newlywed, but then I guess I wasn't average, and that

job was just right for me at that time in my life. Quitting time wasn't until

2 a.m when I would rush to the parking garage, hop in my brand new $2,500 Superbeetle

and zip the 20 miles back home as fast as I could. At least there was no traffic

at that hour--I mean no one, except the cops and the robbers, and an ocassional

jack rabbit staring into my headlights.

One shift in the

wee morning hours when I was delivering the evening's jobs to O'Reilly's office,

I happened to notice a few papers sticking out of his top, right desk drawer.

I opened the drawer in order to push the paper all the way in, lest he think

I had been rummaging through his drawers, when I saw what appeared to be an

illustration of woman. This particular illustration was unusual, because it

was created using nothing more than an "x" in different positions on the page.

I took it out and

unfolded it on the desk. "Figures, she's naked." I thought. When I removed the

computer printout from the drawer, I noticed that lying below it was a printout

of the Mona Lisa. It was great--it looked just like her, and it was made entirely

from x's. "I wonder how O'Reilly did that," I thought to myself.

Opening

the drawer a little further, I found three, one-inch stacks of rubber-banded

punch cards. Hmmm. I jammed over to the keypunch room and dup'ed each of the

three sets of cards, figuring to run them through the computer to see what was

on them and hang on to a set for myself. These "freely distributed" graphics

were 1971's version of today's digital clip art. Guess that makes me one of

the first computer pirates.* Hey O'Reilly, don't tell the Feds. Way cool--1971

computer art.

Opening

the drawer a little further, I found three, one-inch stacks of rubber-banded

punch cards. Hmmm. I jammed over to the keypunch room and dup'ed each of the

three sets of cards, figuring to run them through the computer to see what was

on them and hang on to a set for myself. These "freely distributed" graphics

were 1971's version of today's digital clip art. Guess that makes me one of

the first computer pirates.* Hey O'Reilly, don't tell the Feds. Way cool--1971

computer art.

The next night

after I completed my work, I set about printing more of my new-found treasures,

on company time and paper, no less. I gave them to a few friends, but none shared

the depth of my enthusiasm. I considered that their lack of appreciation must

have been because they didn't understand the process that created the art. "If

they could only see the complexity, yet simplicity of the process," I thought.

One evening, shortly

after my discovery, it was the day shift's quitting time, and I asked my colleague

Marge to stay behind for a minute. "Take a look at this," I said. I grasped

the top sheet of the perforated printout and lifted it to eye level, letting

the life-sized graphic unfold for Marge to see.

"Interesting,

but it'sþwell, so crude," Marge, complained. "Even I can draw better than that."

"You're looking at it too close," I said. "Here, let me hold it up, and you

walk over there by that table." Marge backed up about 10 feet and looked at

the nude again. "Hey, that looks pretty good from here. It's not bad, not bad

at all. I should look that good."

"Interesting,

but it'sþwell, so crude," Marge, complained. "Even I can draw better than that."

"You're looking at it too close," I said. "Here, let me hold it up, and you

walk over there by that table." Marge backed up about 10 feet and looked at

the nude again. "Hey, that looks pretty good from here. It's not bad, not bad

at all. I should look that good."

"Yeah. All I have

to do is take off my glasses," I said, "and make sure I'm 10 feet away."

"Or print littler

x's," said Marge. That Marge, she was always one step ahead of me!

I made a connection

to computer graphics in 1971, but I didn't realize at the time how those experiences

would define the future. In the '70s, I had never heard of anyone making a career

producing computer graphics--after all, the marks on the striped computer paper

were just little x's and 0's, and besides, the art was a sort of underground

thing. I didn't want the boss to find out, or he might think I'd been snooping

in his drawers or something.

That magical night's

events set my imagination on fire. I became intrigued with the beauty of the

binary system, a system of counting that armed the author of a computer program

(which I, assuredly, was not) with the tools to create images that were reasonable

likenesses of real people and objects. From far away, the letters and numbers

on the computer printout were indistinguishable--everything blurred together

to look like a reasonable facscimile of a Christmas tree or Abraham Lincoln,

but up close, you could easily see that the images were really numbers, like

a "1," and a "0," or "x's" arranged on the page to create the "graphic likeness."

Graphics that eventually

beame more commonplace, and then even crude, I find quite remarkable. I appreciate

my direct experience with the "beginnings" of computer graphics and I am equally

amazed with each new discovery, improvement, update and announcement. In 1971

computer graphics was in its infancy--so much potential in all those zeros and

ones and so much more to learn.

Nine years and

two babies after I got my first computer job, I enrolled in a local community

college. I nearly gave up on my idea of creating art and design on the computer

because I didn't want to become a computer programmer or a computer operator--and

I was done with keypunching forever--I knew there had to be a better way to make

a living! My timing could not have been better, for in a few short years, computer

graphics would grow into an entire industry. My jobs working with computers

piqued my interest in graphic design. I was anxious to learn as much as I could

about how to control all those little "spots" on a computer printout. I explored

my education options and decided to study graphic design, process camera, pasteup

and typesetting.

There was actually

a computer graphics degree program, which sounded terrific, but you didn't learn

how to create graphics with the computer. You learned programming--how to create

databases and the like, and then you learned to do graphics the traditional

cut and paste way. That was in 1980, still about 15 years before consumers began

using personal computers. I didn't end up enrolling in the computer graphics

program, but I did enroll in the graphic design program. I figured it wouldn't

hurt to learn something about graphic design until I found a way to make littler

x's.

I spent the next

six years exploring my graphic design and photography interests. Near completion

of the photojournalism coursework in the spring of 1985, I witnessed my first

cataclysmic, mind-blowing demonstration of (yeah, now that's my idea of computer

graphics!) computer graphics. In one, two-hour demonstration, I was captivated,

mesmerized and sold. A week later I used my brand new Macintosh 512k computer

and 300 dpi laser printer to print out the camera ready art for a newsletter,

my first graphic design job produced entirely on my very own "personal" computer.

I never dreamed

that I'd be to be able to create computer graphics in the privacy and convenience

of my own home, without having to "go to work" at night, no less. I could be

home with my kids, who were 10 and 7 by that time. I had been waiting 14 years

for that day. To say I was excited is an understatement. I knew I was onto something

big and I'd be able to figure out a way stay home with my kids and make a living

too--all while I "played" with my new, $14,000 computer. Gulp! What an incredibly

exciting time to be a graphic artist. Never before in the history of communications,

in the history of the human species, has so much technological and social (r)evolution

been packed into so few yearsþand, you ain't seen nothin', yet.

As I write this

introduction, it is the year 2001, and I am still intrigued by and committed

to understanding and teaching computer graphics. Every day some new software

or hardware comes along and blows me away, and even after 30 years working with

computers, the complex technology of the hardware and software continues to

captivate me .

Why use a computer

in the first place?

When I was growing

up in the 1950s, there was no talk of computers. We were the first on our block

to get a television set, not that there was much to watch, but it was amazing

just the same. All the neighbors came to our house to see the new 13-inch, black

and white, moving pictures in a box. The screen was small, the sound was awful

and the box was big. The gang (my big sisters' friends) would gather 'round

the tube, and I'd always squeeze in down front on the floor. There was more

snow than picture, but if I squinted just right, I could make out Spin and Marty

on the Mickey Mouse Club. The technological consumer marvel of the 1950's was

the television.

A couple of years

after we got "TV," I remember the adults sitting around the kitchen table over

coffee and Danish, peppering the conversation with Yiddish words and phrases

when they didn't want us kids to understand. Still no talk about computers.

The hot topic was the threat of nuclear war, and the adults debated building

a bomb shelter in the backyard, just in case. The television set was still black

and white, and "upgrading" in the 1950s meant buying a much bigger set so our

family of eight wouldn't have to crowd so close to the screen.

One evening my

dad came home from work with a special present for the eldest of my sisters--a

transistor radio. Neato! A radio that didn't have to be plugged into the wall--it

ran on batteries, so you could carry it around in your pocket, or at least that

was the hype. The radios were actually pretty big, maybe 5" x 7" x 2", and my

pockets were way too little, giving my sister the perfect excuse not to let

me borrow her new possession. I can remember longing for a radio of my own in

an attractive brown leather case, just like the one my sister carried around

with her. I didn't have a clue then, or for several years, exactly what a transistor

was, let alone the imapct it would continue to have in the field of electronics.

The size of radios

(among other electronic devices) would continue to get smaller as the transistors

shrank in size, while the invention of the integrated circuit assured that the

trend toward smaller components would continue. A few years later, I was introduced

to a computer when I went on a field trip with my junior high school math club

in the early 1960s. The math club rode in the standard issue big yellow schoolbus

to the Bank of America building in downtown Chicago, where a massive mainframe

computer, peripherals, and data processing personnel sprawled across the entire

floor of a Michigan Avenue skyscraper. The air-conditioning unit needed to keep

the equipment at optimum operating temperature was housed beneath the floor

panels and occupied the entire floor below.

I don't think that

people in the '50s and early '60s thought about owning computers, let alone

housing computers, not for $1.6 million and up, not including the airconditioned

skyscraper and taxes. Put a computer in your pocket? Please, get real. The Dick

Tracy watch was pure fiction, no more real than the Starship Enterprise. Take

a look back at the special effects in the early Star Trek episodes, circa 1967,

and by today's standards, you'll find their computers and special effects are

primitive and even amusing.

Today, we carry

internet-ready cell phones in our pockets and purses; not too far off the mark

from the Dick Tracy Watch or Star Trek's "communicator." Of course, Dick Tracy

never had the internet back then.

Technology doesn't

stand still and the one thing we can count on is change. The early 1980s were

a time when barely anyone owned a personal computer, and my husband suggested

we buy an Apple II to help balance our checkbook. I thought that was about the

most ridiculous thing I had ever heard. "Why would I want to spend thousands

of dollars on a computer to balance my checkbook, when I could use my nifty

$249-electronic calculator with a paper tape display to do the same thing?"

I wondered. Buying an expensive computer didn't make the least bit of sense

to me.

It wasn't until

1985, when one of my teachers suggested a much more "practical" use for a home

computer. I quickly became one of the annointed ones--a true believer. That's

when I learned that the computer could be used as a typesetting machine, a process

camera, and a drafting table all in one, and it came with a printer that could

output type and graphics at high enough resolution to be reproduced on a printing

press with excellent quality. What's more, people would pay for the laser prints,

which austensibly circumvented the traditional graphics process. Instead of

contracting one vendor for type galleys, a second for camera work and then cutting

everything apart and pasting it up on boards, we could output the laser prints

from home on a single 812" x 11" sheet of paper and hand them off to the printer

for reproduction.

The technology

was brand new and not yet perfected, but I knew immediately that this was what

I had been waiting for, preparing for, and drawn to since the field trip to

the Bank of America twenty-some-odd years earlier. It was love at first sight,

fate and karma all rolled into one.

The notes presented

here on this website will introduce the reader to the personal computer, personally,

from the point of view of someone who has participated first-hand from the day

the 300 dpi laser printer was introduced.

Goals

These notes should

be of help to beginners, or those who may have skipped some of the fundamentals

in their pursuit of computer graphics and for those who are looking for a refresher

course. Here you'll find a brief history of the computer and its relationship

to the state of computer graphics today. The notes will familiarize readers

with essential design concepts and computer graphics software skills and techniques

using Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, the internet, basic HTML and Dreamweaver,

providing links to other sites when I think it will be helpful.

The notes offer

an introduction and survey to computer graphics software commonly used in the

graphic design and graphic arts fields. The notes are not intended to provide

a complete reference to any of the software programs discussed, but will cover

basic design principles and how to implement them in typical design projects

that utilize scanning, photo collage, illustration, typography and layout.

Strategies are

presented to help students determine the best program to use for specific types

of tasks, as well as presenting strategies for taking your graphic design project

from start to finish, with an emphasis on current computer production processes

and techniques. Students should feel comfortable with the contents of this book

before pursuing more advanced studies in computer graphics, electronic publishing

and mulitmedia.

Platform

The content of

the notes is not platform specific. All of the software covered here is available

and works almost identically on both Macintosh and Windows operating systems.

Therefore, you can use either a Mac or PC to complete the exercises, or both,

provided you save your files in the proper format. You can start on a Mac and

finish on a PC, or vice versa.

Because Apple Computer,

Inc. figures prominently in the phenomonen of "desktop publishing," the graphical

design and interface of the world wide web, and the computer labs of the majority

of computer graphic school programs, it may appear that portions of the book

are skewed toward Apple products; however, every attempt has been made to make

this book as functional and informative as possible to all who want to learn

about computer graphics, regardless of the computer platform.

Macintosh, PC

or personal computer

For the sake of

clairty; references to Macintosh or Macintosh operating system only will be

called Mac, Macintosh or Mac OS, and the IBM-PC or a PC clone running Windows

OS will be referred to as PC or Windows. Personal computer refers to no particular

manufacturer or operating system and can be consider generic in meaning.

Page Format

I began these

notes thinking that some day they would become a book, and perhaps some day

they will. While there are hundreds of great books out there, I couldn't settle

on one or two for a computer graphics survey course. Nothing has the breadth

of material that I wish to, hence these notes presented on the internet will

allow students to take full advantage of my research and explorations, and in

the meantime, I expect make discoveries of your own.

Here, I strive

to provide brain exercises for your journey into the world of computer graphics.

Let these notes be multi-layered like the media they attempt to unravel. You

may find you like the mess-clutter approach of paper scraps and doodles, or

perhaps you'd prefer colored post-it notes so you can add your personal comments,

reminders, or explanations. Print these notes on your home printer, if you like.

Carry your "book" with you and use it as a journal--train your

brain to be creative. Consider the notes a whole system for learning. Let the

layers of information and the connections you make and communicate in your own

unique way transform these notes into your own personal creativity kit. Make

them your own personal goldmine of "connections."

One

night about six weeks into the job, it was work as usual, just like any of the

other long, lonely "swing shifts,"except that night there must have

been a crimp in one of the punch cards. I stood alone in disbelief, while the

computer belched up hundreds of cream-colored 80-column punch cards, spewing

them into the room.

One

night about six weeks into the job, it was work as usual, just like any of the

other long, lonely "swing shifts,"except that night there must have

been a crimp in one of the punch cards. I stood alone in disbelief, while the

computer belched up hundreds of cream-colored 80-column punch cards, spewing

them into the room.  Opening

the drawer a little further, I found three, one-inch stacks of rubber-banded

punch cards. Hmmm. I jammed over to the keypunch room and dup'ed each of the

three sets of cards, figuring to run them through the computer to see what was

on them and hang on to a set for myself. These "freely distributed" graphics

were 1971's version of today's digital clip art. Guess that makes me one of

the first computer pirates.* Hey O'Reilly, don't tell the Feds. Way cool--1971

computer art.

Opening

the drawer a little further, I found three, one-inch stacks of rubber-banded

punch cards. Hmmm. I jammed over to the keypunch room and dup'ed each of the

three sets of cards, figuring to run them through the computer to see what was

on them and hang on to a set for myself. These "freely distributed" graphics

were 1971's version of today's digital clip art. Guess that makes me one of

the first computer pirates.* Hey O'Reilly, don't tell the Feds. Way cool--1971

computer art.  "Interesting,

but it'sþwell, so crude," Marge, complained. "Even I can draw better than that."

"You're looking at it too close," I said. "Here, let me hold it up, and you

walk over there by that table." Marge backed up about 10 feet and looked at

the nude again. "Hey, that looks pretty good from here. It's not bad, not bad

at all. I should look that good."

"Interesting,

but it'sþwell, so crude," Marge, complained. "Even I can draw better than that."

"You're looking at it too close," I said. "Here, let me hold it up, and you

walk over there by that table." Marge backed up about 10 feet and looked at

the nude again. "Hey, that looks pretty good from here. It's not bad, not bad

at all. I should look that good."